Readers Digest 1999, Bruce Selcraig

On a warm morning at a country club near Orlando, a stocky gentleman with wispy gray hair makes his way past the crowd gathered for today’s exhibition. To those who didn’t know better, the impish old fellow could be just another sunburned senior dreaming of bogey golf.

He wears a black turtleneck despite the heat. The left pocket of his neon-lime slacks bulges as always, with two golf balls — never more, never fewer. All three watches on his left wrist are set to the same time.

Taking his position at the tee, he quickly lofts a few short wedge shots about 70 yards. At first the spectators seem unimpressed. Then they notice that the balls are landing on top of one another. “Every shot same as the last,” chirps the golfer, as if to himself, “Same as the last.”

Moving to a longer club, a seven iron, he smoothly launches two dozen balls, which soar 150 yards and come to rest so close ot each other you could cover them with a bedspread. He then pulls out his driver and sends a hail of balls 250 yards away — all clustered on a patch of grass the size of a two-car garage.

Astonished laughter erupts from the crowd. “Perfectly straight,” says the golfer in a singsong voice. “There it goes. Perfectly straight.”

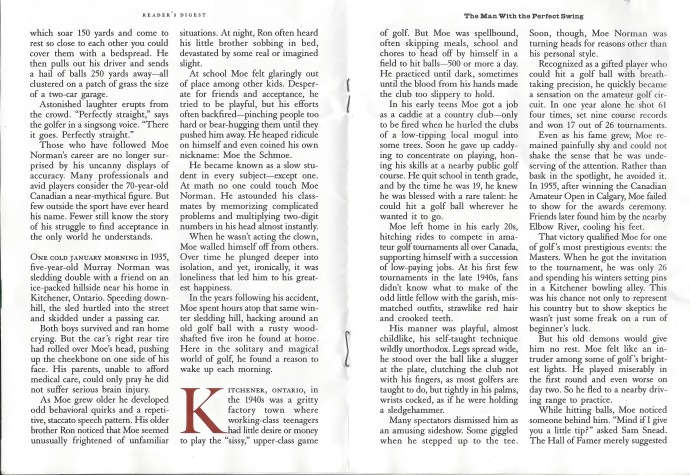

Those who have followed Moe Norman’s career are no longer surprised by his uncanny displays of accuracy. Many professionals and avid players consider the 70-year-old Canadian a near-mythical figure. But few outside the sport have ever heard his name. Fewer still know the story of his struggle to find acceptance in the only world he understands.

One cold January Morning in 1935, five-year-old Murray Norman was sledding double with af riend on an ice-packed hillside near his home in Kitchener, Ontario. Speeding downhill, the sled hurtled into the street and skidded under a passing car.

Both boys survived and ran home crying. But the car’s right rear tire had rolled over MOe’s head, pushing up the cheekbone on one side of his face. His parents, unable to afford medical care, could only pray he did not suffer serious brain injury.

As Moe grew older, he developed odd behavioral quirks and a repetitive, staccato speech pattern. His older brother Ron noticed that Moe seemed unusually frightened of unfamiliar situations. At night, Ron often heard his little brother sobbing in bed, devastated by some real or imagined slight.

At school, Moe felt glaringly out of place among other kids. Desperate for friends and acceptance, he tried to be playful, but his efforts often backfired — pinching people too hard or bear-hugging them until they pushed him away. He heaped ridicule on himself and even coined his own nickname: Moe the Schmoe.

He became known as a slow student in every subject — except one. At math, no one could touch Moe Norman. He astounded his classmates by memorizing complicated problems and multiplying two-digit numbers in his head almost instantly.

When he wasn’t acting the lown, Moe walled himself off from others. Over time, he plunged deeper into isolation, and yet, ironically, it was loneliness that led him to his greatest happiness.

In the years following his accident, Moe spent hours atop that same winter sledding hill, hacking around an old golf ball with a rusty woodshafted five iron he found at home. Here in the solitary and magical world of golf, he found a reason to wake up each morning.

Kitchener, Ontario, in the 1940s was a gritty factory town where working-class teenagers had little desire or money to play the “sissy,” upper-class game of golf. But Moe was spellbound, often skipping meals, school and chores to head off by himself in a field to hit balls — 500 or more a day. He practiced until dark, sometimes until the blood from his hands made the club too slippery to hold.

In his early teens Moe got a job as a caddie at a country club — only to be fired when he hurled the clubs of a low-tipping local mogul into some trees. Soon, he gave up caddying to concentrate on playing, honing his skills at a nearby public golf course. He quit school in tenth grade, and by the time he was 19, he knew he was blessed with a rare talent: he could hit a golf ball wherever he wanted it to go.

Moe left home in his early 20s hitching rides to compete in amateur golf tournaments all over Canada, supporting himself with a succession of low-paying jobs. At his first few tournaments in the late 1940s, fans didn’t know what to make of the odd little fellow with the garish, mismatched outfits, strawlike red hair and crooked teeth.

His manner was playful, almost childlike, his self-taught technique wildly unorthodox. Legs spread wide, he stood over the ball like a slugger at the plate, clutching the club not with his fingers, as most golfers are taught to do, but tightly in his palms, wrists cocked, as if he were holding a sledgehammer.

Many spectators dismissed him as an amazing sideshow. Some giggled when he stepped up to the tee. Soon, though, Moe Norman was turning heads for reasons other than his personal style.

Recognized as a gifted player who could hit a golf ball with breathtaking precision, he quickly became a sensation on the amateur golf circuit. In one year alone he shot 61 four times, set nine course records and won 17 out of 26 tournaments.

Even as his fame grew, Moe remained painfully shy and could not shake the sense that he was undeserving of the attention. Rather than bask in the spotlight, he avoided it. In 1955, after winning the Canadian Amateur Open in Calgary, Moe failed to show for the awards ceremony. Friends later found him by the nearby Elbow river, cooling his feet.

That victory qualified Moe for one of golf’s most prestigious events: the Masters. When he got the invitation to the tournament, he was only 26 and spending his winters setting pins in a Kitchener bowling alley. This was his chance not only to represent his country but to show skeptics he wasn’t some freak on a run of beginner’s luck.

But his old demons would give him no rest. Moe felt like an intruder among some of golf’s brightest lights. He played miserably in the first round and even worse on day two. So he fled to a nearby driving range to practice.

While hitting balls, Moe noticed someone behind him. “Mind if I give you a little tip?” asked Sam Snead. The Hall of Famer merely suggested a slight change in his long-iron stroke. But for Moe it was like Moses bringing an 11th commandment down from the mountaintops.

Determined to put Snead’s advice to good use, Moe stayed on the range until dark, hitting balls by the hundreds. His hands became raw and blistered. The next day, unable to hold a club, he withdrew from his Masters humiliated.

But Moe climbed right back up the ladder to win the Canadian Amateur again a year later. A string of victories followed. In Time, he had won so many tournaments and collected so many televisions, wristwatches and other prizes that he began selling off those he didn’t want.

When the Royal Canadian Golf Association charged him with accepting donations for travel expenses, which was against regulations for Amateurs, Moe decided to turn professional. His first move as a pro was to enter, and win, the Ontario Open.

As a newcomer to professional golf, Moe approached the game with the same impish lightheartedness of his amateur years. When people laughed, he played along by acting the clown. An extremely fast player, he’d set up and make his shot in about three seconds, then sometimes stretch out on the fairway and pretend to doze until the other players caught up.

Fans loved the show, but some of his fellow competitors on the US PGA Tour did not. At the Los Angeles Open in 1959, a small group of players cornered Moe in the locker room. Stop goofing off, they told him, demanding that he improve his technique as well as his wardrobe.

Friends say a shadow fell across Moe that day. Some believe the episode shattered his self-confidence and persuaded him to back out of the American tour, never to return. More than anything, Moe had wanted to be accepted by the players he so admired. But he was unlike the others, and now he was being punished for it.

The laughter suddenly seemed barbed nad personal. No longer could he shrug it off when some jerk in the galleries mimicked his high-pitched voice or hitched up his waistlines to mock Moe’s too-short trousers.

Because Moe never dueled the likes of Americans Jack Nicklaus or Arnold Palmer, he achieved little recognition beyond Canada. At home, though, his success was staggering. On the Canadian PGA Tour and in smaller events in Florida, Moe won 54 tournaments and set 33 course records .While most world-class golfers count their lifetime holes-in-one on a few fingers, Moe has scored at least 17.

Despite his fame and the passing years, Moe was continually buffeted by the mood swings that tormented him in childhood. Even among friends he could be curt, sometimes embarrassingly rude. At other times, he was charming, lovable Moe, bearhugging friends and tossing golf balls to children like candy — the happy-go-lucky clown from the amateur days.

Through the 1960s and 70s Moe racked up one tournament victory after another, But in the early 1980s, his enthusiasm for competition began to wane. His winnings dwindled, and he slipped into depression. Not being wealthy, he seemed to care very little for money, lending thousands to aspiring golfers and never bothering to collect.

Broke and all but forgotten, he drifted from shabby apartments and boardinghouses to cut-rate roadside motels, often sleeping in his car. Had it not been for the generosity of friends — and a stroke of good luck — he might have faded entirely into obscurity.

Moe has never had a telephone, a credit card or owned a house. Few people know where he might be living on any given day, and he seldom talks to strangers. Little wonder it took Jack Kuykendall two years to track him down.

Kuykendall, founder of a company called Natural Golf Corp., finally caught up with him in Titusville, Fla. He told Moe that, trained in physics, he had worked for years to develop the perfect golf swing — only to discover that an old-timer from Canada had been using the same technique for 40 years. He had to meet this man.

Moe agreed to demonstrate his swing at clinics sponsored by Natural Golf Corp. Word spread quickly through the golfing grapevine, and before long, sports magazines were trumpeting the mysterious genius with the killer swing. Among those following Moe’s story was Wally Uihlein, president of the golf-ball company Titleist and Foot Joy Worldwide. Hoping to preserve one of golf’s treasures, Uihlein announced in 1995 that his company was awarding Norman $5000 a month for the rest of his life. Stunned, Moe asked what he had to do to earn the money. “Nothing,” said Uihlein, “you’ve already done it.”

Two weeks later, Moe Norman was elected to the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame. Even today, however, he remains largely unknown outside his native country except among true disciples of the game. For them, Moe is golf’s greatest unsung hero, the enigmatic loner once described by golfer Lee Trevino as “The best ball-striker I ever saw come down the pike.” Many agree with Jack Kuykendall — had someone given Moe a hand 40 years ago, “we would know his name like we know Babe Ruth’s.”

In the parking lot of a Florida country club, Moe Norman is leaning into his gray Cadillac, fumbling through a pile of motivational tapes. He seems nervous and rushed, but as he slides behind the wheel, he pauses to reflect on his life, his family and his obsession.

Moe never had a real mentor, or a trusted adviser. “Today’s kids,” he says, “are driven right up to the country club. Nice golf shoes, twenty-dollar gloves, nice pants. ‘Have a nice day, son.’ I cry when I hear that. Oooh, if I’d ever heard that when I was growing up…”

He squints into the sun and cocks his head. “Everyone wanted me to be happy their way,” he says. “But I did it my way. Now, every night I sit in the corner of my room in the dark before I go to bed and say, ‘My life belongs to me. My life belongs to me.'”

With that, he shuts the door and rolls down the window just a crack. Asked where he’s going, Moe brightens instantly, and a look of delight spreads across his face.

“Gone to hit balls,” he says, pulling away. “Hit balls.”

It is, and forever will be, the highlight of his day.

What a terrific article. It never ceases to amaze me how cruel people can be to one another when they either do not understand a person or a concept.

LikeLike

Again I say thank you Todd. I am enjoying these postings so much.

LikeLike

Your welcome Dave!

LikeLike

The article makes one admire Moe even more. Thanks for sharing Todd.

LikeLike

Nice story Todd. I enjoyed it. That kid sitting next to Moe… is that really you? Amazing!!

LikeLike

Wow I look young. How time flies.

LikeLike

Todd — on one level this is such a sad story of a man with such greatness kept from so many in the world in part because of how we can be so harsh in judging anyone “different” from the accepted norm. On another level, this is an inspirational story that would benefit those both inside and outside the golfing world. To find one’s passion and to devote one’s life to it, achieving a level of mastery that gives one personal joy, while learning to ignore anyone who may pass judgement on oneself and one’s unusual ways — we should all live life in that way and embrace each other for our uniqueness.

I have watched several of your videos of Moe and come to care for him greatly. I only wish he were still with us. Fortunately, we are blessed to have you and your devotion to sharing his greatness, studying and learning his swing to then teach it to others. I found you last year when searching out golf instruction and plan to focus my efforts this year on learning the single plane golf swing after having experimented with many different techniques last year. Hope to meet you at one of your schools this year.

LikeLike

Thank you Craig.

Moe was a great example of “be yourself”. Yes, we should all follow our own path. I think Moe suffered some for his uniqueness but he kept on being himself and doing it his way. He is inspiring. I look forward to meeting you at a school program this year.

Todd

LikeLike

What an amazing life ! Robert Redford (The legend of Bagger Vance) or Clint Eastwood ( Million dollar baby) would make a beautiful movie about Moe’s brilliant personnality. Thank you to continue his Masterpiece and help many golfers to get fun on the course. Since I discovered the single plane and every time I hit a good shot, I’m thinking “Thanks Moe, thanks Todd”. The more I repeat it the better my scores ! 🙂

LikeLike

It is difficult to get enough of stories about Moe Norman. Like Hogan, he invented this way of swinging and that alone makes him a genius. An inspiration to every golfer with passion to improve.

LikeLike

Fantastic article. Moe’s swing and Geaves instructional videos have changed my game from a 30 hcp to current 14hcp and made the golf fun! Thank u Moe, Todd and Tim Graves!

LikeLike